Success and Failure in M&A Execution – An Empirical Study

By GPMIP Benelux Associate Partner, Fabrice Lobet and Partner, Christophe Van Gampelaere

This study is also available in Dutch and French.

We hear time and again the mantra that “two thirds of mergers fail to achieve the intended goal.” In a series of expert notes based on big data analytics, the authors set out to test this hypothesis, and to seek the answer to the question: “What is needed to achieve M&A success?” This first article offers an in-depth reality check on how successful public companies are in the field of M&A. The next article will dive deeper into the facts as they apply to private companies. The series then continues with qualitative insights and recommendations on how to reduce the risk of M&A execution failure.

Over the past decade, the debate on the success rate of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) has drawn great attention amongst professionals as well as in the academic world. With billions of Euros invested each year, understanding why deals fail and succeed remains as crucial as ever.

Today, liquid markets and low interest rates have triggered a new wave of M&A transactions. External growth strategies have become popular, even amongst small and medium sized businesses. Markets are more transparent and investors more informed. As a result, transactions are easier to close and should be safer to implement than in the past.

Nevertheless, recent statistics and studies stubbornly keep sending out the same old message, namely that:

“Most M&A deals fail.” (60 to 80 per cent in fact, depending on the studies).

To put the word “fail” into perspective, the message should read:

“Most M&A deals do not manage to make up for the cost of the acquisition and the destruction of shareholder value.”

In other words, one plus one does not even equal two, whereas three was intended. The fact that most M&A operations are doomed to destroy value has become a paradigm – and a paradox – today.

Studies supporting the case almost exclusively deal with publicly listed companies and use just one major indicator: the evolution of the market capitalisation before and after the deal, which in itself may already imply some bias.

Does M&A really destroy value? How and why? Are acquirers sufficiently prepared? Do they pay the right price? Are they doing enough in the weeks and months before and after the closing? What are the hidden risk factors?

The authors will deal with these questions in a series of study installments, mixing big data analysis with on-the-ground expertise in M&A strategy and integration. First of all, let’s validate and understand the mechanisms of value destruction.

Do most M&A operations destroy shareholder value?

The case of publicly listed acquirers worldwide

First we set out to test the generally accepted market capitalisation (“market cap”) paradigm. We analysed 11,000 transactions, executed between 2010 and 2017, and involving publicly listed companies acquiring a majority stake. We eliminated serial acquirers and companies buying more than one target from the sample, as these may cause bias related to the interference of other deals.

Methodological note: measuring (expected or perceived) value creation

The study mainly deals with the Value Recognition Index (VRI), calculated on the basis of the acquirer’s Market Capitalisation (MC) and the Transaction Price (TP) paid for the target company. The index is calculated as follows:

VRI (%) = [(MC2/(MC1+TP))-1]*100

Where MC1 = acquirer’s market capitalisation the day prior to the rumour or announcement

TP = transaction price paid for the target

MC2 = market capitalization one week after closing of the deal

All other things being equal, a VRI greater than 0 means that the value of the transaction, as recognised by investors, is higher than the price actually paid for the target. In the eyes of investors, the transaction will create additional value. Conversely, a negative VRI implies expectations of value destruction amongst investors.

The financial and transaction data are collected from Orbis, an information tool developed by Bureau van Dijk (a Moody’s company), and analysed by Global PMI Partners.

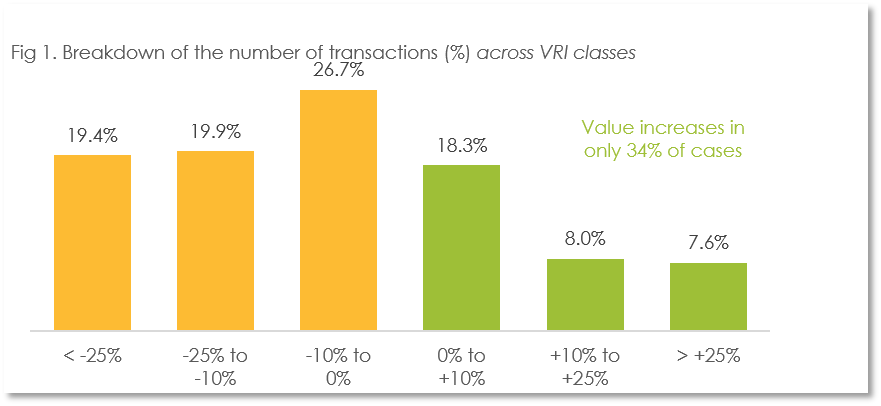

From a remaining dataset of 7,059 acquisitions, we found that in only one out of every three cases, the price paid by the acquirer was passed on to the investor, by means of an increase in share value (a positive VRI).

Worse still, in 39 per cent of the deals, the market cap decreased by more than 10 per cent between the rumour/announcement and the closing dates (Fig. 1).

Source: Orbis (Bureau van Dijk), Global PMI Partners calculation and analysis, © GPMIP 2018

Those figures tend to confirm the conclusions of the literature. However, behind this general pattern hide various realities.

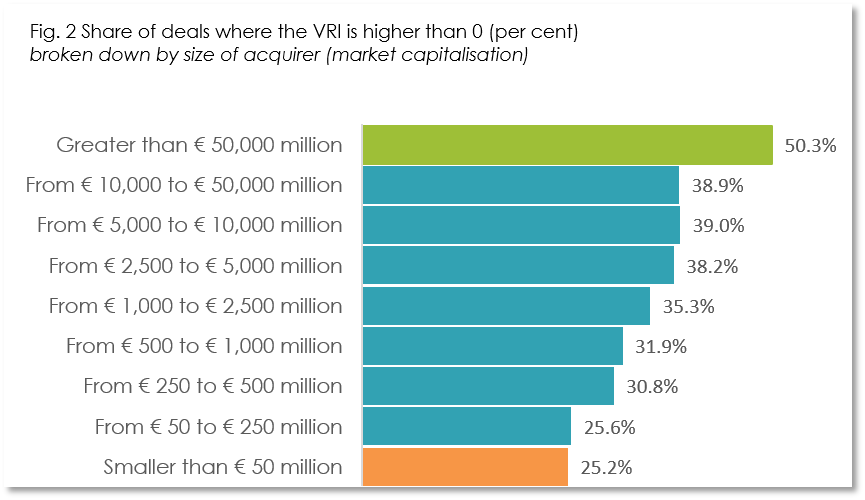

Breakdown by acquirer size

Source: Orbis (Bureau van Dijk), Global PMI Partners calculation and analysis, © GPMIP 2018

First, there is a positive correlation between the size of the acquirer and the level of value recognition. Fig. 2 shows that the larger the acquirer, the more likely the investor will believe in a successful outcome. Indeed, big organisations are deemed to be more able to make expected value gains come true. They may be more likely to allocate the necessary resources to manage the integration and synergies, they may incentivise their teams more effectively, or perhaps they are better at sheer project management. As they become larger, they may benefit more from economies of scale, both on the supply side, and on the delivery side.

When strategy pays

When Jack Link’s acquired the Bifi and Peperami brands from Unilever in 2014, there was a clear strategic rationale, namely to establish a beachhead for expansion into EMEA. The company acquired an existing infrastructure and was subsequently able to not only sell the Unilever sausage snacks, but also to include their own beef jerky snacks.

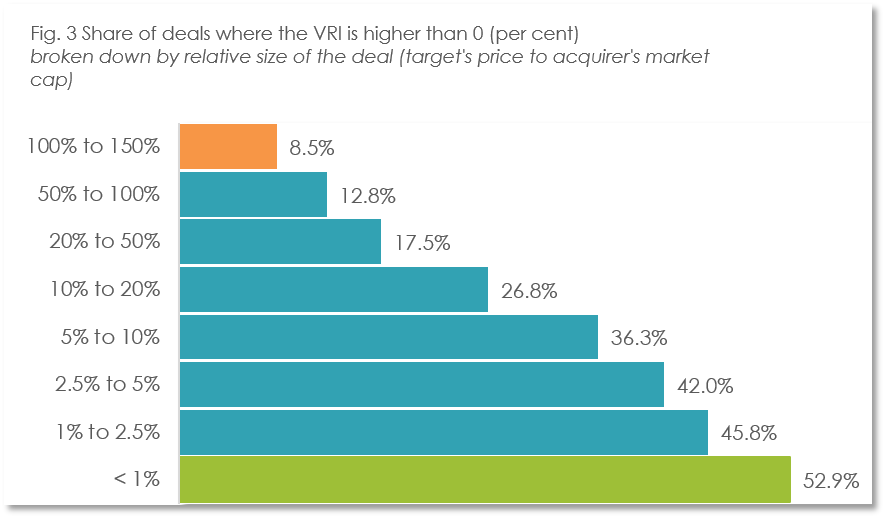

Breakdown by relative deal size

There is an even stronger correlation between the relative deal size – i.e. target price to acquirer’s market cap – and the recognition of the deal value by investors (Fig. 3). The higher the size gap between target and acquirer, the higher the chances that the target price is incorporated in the acquirer’s valuation. Relatively smaller targets are indeed easier to digest, causing minor disruption to the acquirer’s business. Too big a target, on the other hand, and investors may raise suspicion as to the acquirer’s ability to generate value.

Big organisations are deemed to be more able to realise value gains than smaller ones. The largest companies manage to increase value with 50%.

Source: Orbis (Bureau van Dijk), Global PMI Partners calculation and analysis, © GPMIP 2018

When you bite off more than you can chew

The ability to successfully process a transaction depends on various factors, such as clarity of strategy, adequate resourcing, incentivisation, focus on culture and sheer skill. We have seen deals falter for a lack in any or all of these factors. The bigger the size of the target, the more relevant it is to be prepared on all fronts. A particular example is the case of a large French publisher buying its rival of equal size. In order to win the bidding war, the acquirer needed to convince bank lenders to provide more deal financing. Based on the envisaged synergies, banks agreed. Once the deal closed, the acquirer’s management decreed that the integration of the two businesses would be put off for the foreseeable future. Financial synergies were subsequently not realised, and the company was unable to honour the bank covenants. For the first time in the company’s history, an external investor had to be allowed in, in order to bail the company out.

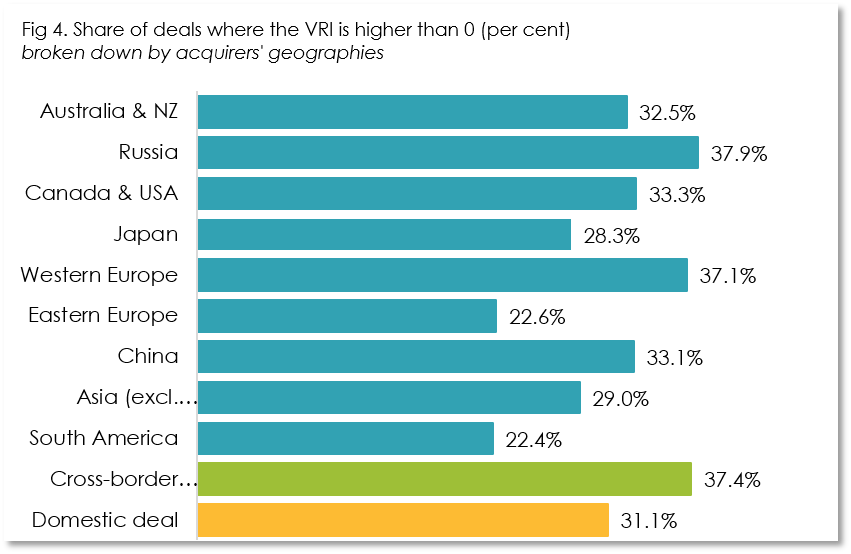

Most acquirers (70 per cent) remain focused on domestic markets when it comes to M&A. The figure drops to 52 per cent for the larger acquirers, i.e. those with a market cap above € 10 billion. Understandingly, the bigger the acquirer, the more likely he is to focus on foreign markets. However, it seems that even for large businesses, the home market remains the privileged hunting ground. Legal and cultural contexts are better understood, and proximity may play a role too. Paradoxically, investors seem to be more inclined to recognise the value of cross-border deals (Fig. 4). Causes for this are to be found in the greater diversification these deals offer, as well as in the fact that larger organisations are more involved in such deals than smaller ones. The sheer size of the acquirer’s business will impact the target value recognition (Fig. 2).

Breakdown by geography

Is there a difference related to geography? We found that deals closed by acquirers located in Western countries are better appraised than deals closed by emerging market companies, with Russia and China being exceptions. This may partly be due to the longer track records and a greater presence of experienced deal professionals in the West.

Source: Orbis (Bureau van Dijk), Global PMI Partners calculation and analysis, © GPMIP 2018

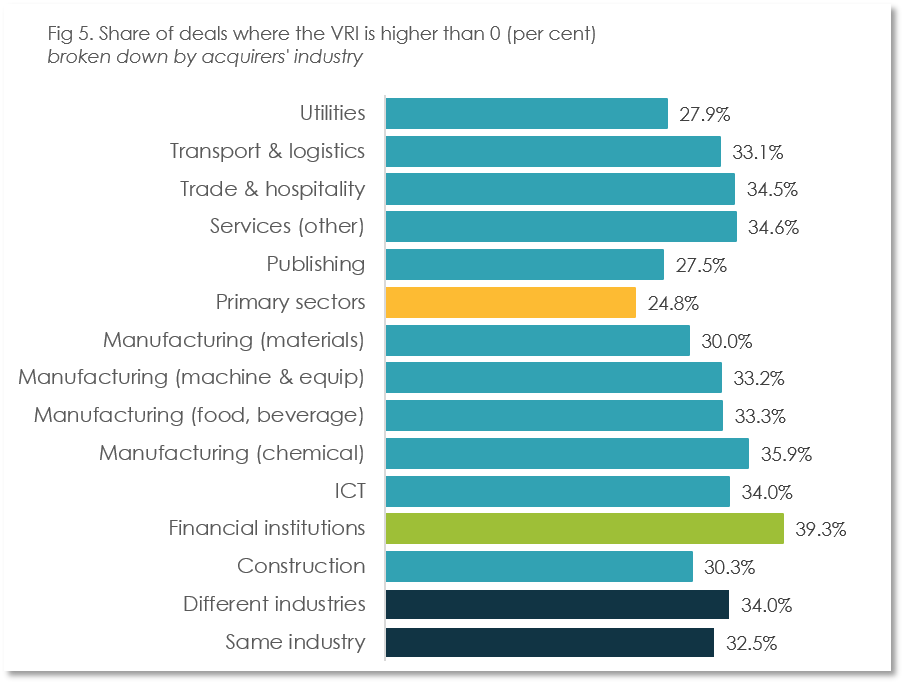

Breakdown by industry

Vertical or horizontal integration are common determinants of an M&A strategy. The fact whether or not a deal involves counterparties from the same industry does not significantly affect the post-deal market cap increase and the VRI (Fig. 5). At a more detailed level, the indicator varies within quite a narrow margin, with a few exceptions: financial institutions (higher degree of value recognition) and primary industries (a lower indicator).

Source: Orbis (Bureau van Dijk), Global PMI Partners calculation and analysis, © GPMIP 2018

It transpires from our analysis that external growth projects do not generally win acceptance from investors. Several reasons can be put forward, being of either a subjective or an objective nature.

A company’s valuation is a reflection of the collective and subjective opinion of investors. In the same way, failure to recognise the value of an acquisition on the part of investors may be driven by various qualitative factors such as misinformation, a lack of confidence in the management’s ability to realise promised synergies, the lack of understanding of the deal’s rationale, inadequate communication, or quite simply the non-adhesion to a corporate project. It regards in fact all the elements that will affect and define the investors’ perception. Our experience in transaction integrations leads us to believe that these elements, although not quantifiable, are far from negligible. In other words, the investors’ perception is not necessarily disconnected from reality.

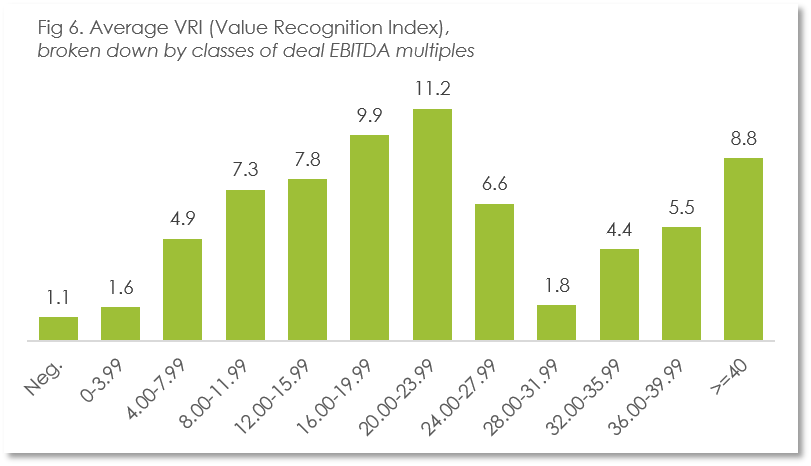

Breakdown by EBITDA multiple paid

The price paid for the target may just be too high, according to market standards, or compared to past performance. In this case, is there a relationship between price recognition by investors (VRI) and a price indicator such as the multiple paid? The analysis (Fig. 6) does not provide clear support to one assumption or the other. Several factors come into play and make a one-to-one interpretation impossible.

Source: Orbis (Bureau van Dijk), Global PMI Partners calculation and analysis, © GPMIP 2018

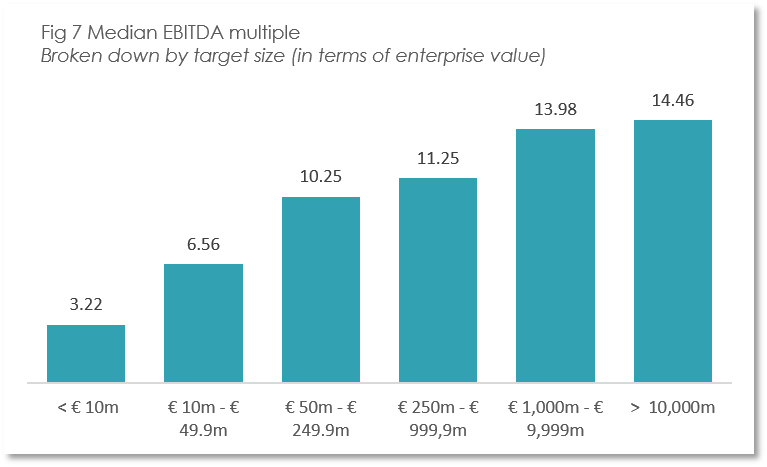

On the one hand, higher multiples are rewarded by a surplus value of the market capitalisation and a higher VRI, to a certain extent. The logic behind this is that, statistically, larger acquirers buy larger targets. And there exists a positive and linear relationship between the target size and the multiple paid (Fig. 7). The acquirer is inclined to pay more for a larger target, which is supposedly better established, better functioning and therefore less risky. This is called the size premium. Companies buying such a target are generally bigger and thus, more able to manage value creation through M&A, as concluded earlier. In such a context, it is understandable that investors recognize a high price and passed it on to the acquirer’s share price.

Source: Orbis (Bureau van Dijk), Global PMI Partners calculation and analysis, © GPMIP 2018

On the other hand, this could be thwarted by investors penalizing the acquirer for spending too much money in the acquisition of a target, as conditions described above are no longer applicable. This is certainly the case when the relative size of an acquisition is high, compared to the acquirer’s.

According to financial theory, the intrinsic value of a business is mainly driven by future performance, to which the benefits of the expected synergies needs to be added. The next article in our study series will discuss the extent to which financial indicators of both acquirer and target are likely to improve – or not.

Conclusion

Our study confirms the findings in most other papers.

The evolution of the market capitalisation of publicly listed companies following an acquisition generally points to a destruction of shareholder value.

Differentiations by geography, by industry, by relative deal size, or by acquirer size do not point.

The very operating model of public organisations causes a more acute level of potential agency conflict, where the incentives of the acquirer’s top management trump any benefit to the public shareholder.

As shareholders are aware of this, they vote with their wallet, and sell the stock, brining down the share price. In the following studies, subjective elements will be partly neutralized by analysing private companies, with fewer or inexistent agency conflicts. Stay tuned for more.

The question we pose next is this one:

The next installment of our study will essentially deal with unlisted companies, where the ownership structure is simpler and consequently less subject to agency conflicts.

That analysis will allow us to answer the questions: is there not a significant implied bias in these results from public companies? What is the impact on shareholder value over a longer period of time?

What are your thoughts on success and failure in M&A execution? Comment and “Like” this post on LinkedIn by clicking here.

About Global PMI Partners

Global PMI Partners is the only global consultancy firm focused exclusively on merger integration and carve-out services. With offices across the US, Europe and Asia, Global PMI supports both private equity as well as corporate acquirers.