Role of Leadership and Change Management in M&A

By Chris Charlton, UK Partner at Global PMI Partners

There is a need to constantly develop our skills and understanding, no matter who we are, what we do, who we do it for or where we do it. To understand, appreciate and work with other people is the key to most of what we achieve in life. Whatever our goals and aspirations, be they personal or professional, a sound understanding, and application of the skills of leadership and change management can make the difference between our success and failure.

But are these possible to learn or improve, as it is often argued that many of these skills are of an innate nature?

It should be obvious that the quality of a leader’s or manager’s own personal experience is going to be a crucial factor. Considerable demands may be made on our powers of judgement and decision-making at times, and to be effective, it is necessary to be able to call upon a sound foundation of solid personal experience. There is no substitute for actual personal experience and there are no short cuts to the gaining of it. But there is also no substitute for the wisdom and experience of others, whether hired externally or by building capability through knowledge sharing.

In the beginning, management learning and development simply happened. Leaders and managers weren’t dispatched on training courses, they learned by coming through the ranks. The job taught them everything they needed to know. Technical excellence often led to management positions, without the recognition that this requires a different set of skills. This view appears to be an artefact of ancient history. It isn’t. Though the world has become crowded with business schools and training companies, management development is still a relatively new practice.

This contrasts significantly with the centuries spent educating lawyers, engineers, clerics, soldiers, teachers and doctors in formal, recognised institutions. More recently, management has begun to claw back the ground lost. Most business schools, though, generally provide a traditional emphasis on finance and strategy rather than the “softer” side of management.

There is an increasing awareness of the importance of giving ‘people issues’ attention and consideration equal to that traditionally given to financial, logistical, and other business-related issues. The real methods, or ‘how to’, of addressing people issues, though, are not yet well established. However, there is an enormous body of experience available to us from all walks of life – business, sport, politics, military, history, the world and all its cultures, if only we choose to look and learn. The key is knowing what works, plus having the confidence to apply these skills when it is beneficial to do so.

Leadership is one of the great intangibles of our world. It is a skill most people would love to possess, but one which defies clear or consistent definition. Ask people which leaders they admire, and you are as likely to be told Gandhi as John Kennedy, Jack Welch or Sir Alex Ferguson. Yet, most agree that leadership is a vital ingredient for success, business or otherwise, and that great leaders make for great organisations.

Interestingly, and unhelpfully for the practising manager, leadership attracts many aphorisms rather than hard and fast definitions. Indeed, there is a plethora of definitions of what constitutes a leader and the characteristics of leadership. In practice, none has come to be universally, or even widely, accepted. For example, the very individualism associated with leadership is now a bone of contention. Some of the people we tend to think of as leaders — from Napoleon to Winston Churchill — are not exactly renowned for their team-working skills.

But today’s leaders have to be pragmatic and flexible to survive. Increasingly, this means being people- as well as task-oriented. Whilst the prime role for a leader can arguably be stated as ‘getting the job done!’, in a situation such as an M&A project environment, it is vital for effective relationships to exist between the project manager, individuals and the team, if success is to be achieved. The leadership function is therefore not only getting the job done, but also developing those effective relationships.

The ‘great man’ theory about leadership rarely applies — if teams are what make businesses and organisations run, then perhaps we also have to look beyond individual leaders to groups of people with a variety of leadership skills. Successful leadership in organisations is more than just the skills and characteristics of the person at the top of the pyramid. If you’re ambitious, you probably envision yourself becoming a leader, an individual who others respect and follow, which involves understanding and honing a mix of traits and skills that you can develop at any time and that will help move you up the ladder. And if you’re already a seasoned leader, then you’re likely to considering the next leadership challenge, and what you need to know to accomplish it successfully. After all, great corporate leaders are always hungry to know more and do not regard their knowledge as static or comprehensive.

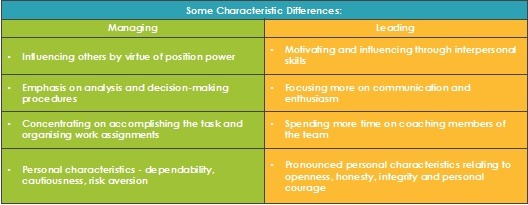

Leading v Managing?

What about the distinction between managing and leading? Probably the simplest distinction is between getting others to do and getting others to want to do. Managers have used extrinsic rewards and pressures such as promotions, bonuses, and titles to get others to do things for many decades. Leaders get people on their team to want to do, by establishing a clearly stated inspiring vision arrived at jointly with the team, by empowering the team, by expanding their authority, and by continually communicating his or her heartfelt belief in the project or organisation mission.

Leadership Characteristics

To fully understand leadership and be good at it, you must be highly aware and cognisant of three things: firstly, yourself; secondly, other people, in particular those you wish to lead; and finally, how you relate and interact with those other people. This means not just observing what people do or want to do, but more importantly, why and how. A deep understanding of basic human psychology can be a huge asset to a leader, as the more you are able to anticipate, interpret and motivate the behaviours of others, the more you will be able to select the most appropriate style, skill or tool for a given situation.

This implies a very articulate grasp of a situation which only a process of reflective self-analysis and self-questioning about a leader’s own experience will give. It is not enough to know the right thing to do. A leader must know why it is right and what the consequences will be if it is done incorrectly or differently.

Leaders need to have examined their personal reasons and motives for wanting to lead, and to what ends. For example, leadership used to inflate the ego, such as needing to demonstrate expertise and ‘superior’ powers to a group, can be a destructive exercise without value to the people of that group. There needs to be a clear realisation that the responsibilities of leadership may impose a discipline that allows very little room for personal wishes, ambitions or aspirations. Leadership in this context is a state of mind that can be largely selfless, aside from the reward of leading itself.

As a leader, the better you can understand other peoples’ motivations, actions and behaviours, the more able you are to plan your own actions and strategies to align your preferred outcome with the needs and expectations of others. A leader who is unaware of, or unsympathetic to the group is likely going to be a disappointed, frustrated person and a bad leader. Very rarely will the motives, ambitions, interest and capabilities of a group coincide with those of the leader.

A leader’s concept of the role should not consist solely in imparting as much technical know-how to the group as possible or over-focus on the task in hand. There is more to life. Time should be given for the aesthetic and emotional feelings, to impinge on the awareness of those in the group for whom such things may have meaning and great importance. Any snippet of information about what is going on is also worthwhile. Curiosity starved often dies quickly. Feed it and the results are often very surprising and fruitful.

A leader has the responsibility and authority for making the final decision. He may not always get credit when things go right, but he’ll get the blame when things go wrong. So, it’s critical to have a total grasp of the situation before making decisions. So, you must become aware of the way you manage relationships in a leadership situation.

This will give a great advantage in the art of dealing with and relating to people; the skills and intricacies of communication; the relieving of tension, of using humour; of understanding the dynamics of group life and encouraging the full development of the individuals in your group; of fostering self-sufficiency, confidence and self-determination in people.

For some leaders, one of the most difficult problems to conquer is when they actually reach the top – the ivory tower syndrome, or executive isolation. The farther a manager moves from the roots of the business, the harder it is to keep up with what’s happening in that business. Most executives work and live and lunch and play golf or tennis with the same people. That means that all of their person-to-person contact is with people who largely live, work, and think alike. This gradual isolation from other people is a trap that could easily remove the leader from a sound position of understanding those other people and the chance to utilise the dynamics of interaction.

Sample Leadership Attributes

Positive Mental Attitude

In all relationships, a good leader retains a positive mental attitude. This is composed of faith, optimism, hope, integrity, initiative, courage, generosity, tolerance, tact, kindness, and good sense. This is the most personal of principles. Only you – and you alone – can control what your mind accepts or rejects. You know that you may face a barrage of negative influences every day. But the ability to remain positive in difficult scenarios can make you stand out from the crowd. Optimism, enthusiasm and courage are powerful, compelling forces that draw other people closer, even stop and listen.

Leadership Styles

Do you always manage situations and solve problems using the same style? Do you stop and think about the approach you are using, or do you habitually attack most challenges in the same mode? Leaders and managers must learn to stop and think about which style they are going to apply to a given situation, and to be cognizant of why they have chosen that style. The approach chosen should correspond to the needs of the situation. For example, would you want a participatory style of leadership if you were a passenger in a nose-diving airplane?

Some leadership styles are easily identifiable.

Setting an Example

There is leadership by example – a force pulling a team along from the front. One of the most important moves a leader can make is to set the right example, as you set an example whether you want to or not. The trick is to set a good example, to be what you want others to be. Example is important because people take in information more through their eyes than through their ears. What they see you do has a far greater impact than what they hear you say. Word and example must match up, must not conflict.

If bosses set office hours from nine to five, but show up at ten and leave at four, if the mistakes of others are fodder for public discussion, but theirs are never mentioned, expect that behaviour to become contagious. Then the team will realise it is impossible to follow the leader’s example without getting into trouble, and they will become frustrated.

A good leader uses creative power to demonstrate the behaviours they want their team to emulate. Seeing this can work in people’s minds to alter their ways, especially if it involves an element of self-sacrifice. The process may take time, but the leader whose example backs up his words puts himself in an unassailable position. No one can accuse him or her of hypocrisy.

Francis Bacon said it well: “He that gives good advice builds with one hand. He that gives good counsel and example builds with both. But he that gives good admonition and bad example builds with one hand and pulls down with the other.”

If leaders are highly skilled and competent, they may be so far removed from the level of skill in the team or group that they are unaware of, or unsympathetic to, any difficulties they may be experiencing. Being at the front, they may tend to take all the decisions all the time. The group may hardly be involved in the experience and will tend to be tagging along blindly. A leader in this situation will have to be wary that the team or group will have no real idea of what is happening, or why, where and how. This can lead to a rapid loss of motivation and control, therefore the skill of leading from the front in this situation is constant awareness of the team, coaching where required, and the gradual raising of standards, expectations and performance.

Giving Encouragement

There is leadership from the rear – a force pushing the team from the back. The concern here may be to allow the team to feel they are involved and exercising some initiative in the shape of the day, mission or objective. There is also present a humane concern to encourage the weaker ones who tend to be in the rear. The danger is the leader’s potential loss of control at the front unless some thought has been given to the problem. Knowledge of the team needs to be good enough to be able to rely on them as necessary to the situation. The skill is then to maintain enthusiasm and enjoyment without losing control of the outcome.

Democratic or Group Facilitation

There is leadership from the middle. This style tends to work where the leader is able to allow the group to resolve their different impulses and inclinations, to decide for themselves, to adapt and carry through their plans. The group is helped to lead itself as far as it is judged capable of doing so. The leader is watchful to give support, encouragement, sympathy guidance or advice to those individuals who need help, or where the team needs direction.

The leadership skill is to facilitate the optimum utilisation of skills and knowledge of the team or organisation by drawing out the best input from everyone involved.

Autocratic or Dictatorship

The leader will only be authoritarian or military in style at those times when the occasion or situation demands it. For example, this style will be used sparingly by a mountain leader only in emergencies or when physical safety is threatened by ignorance or foolhardiness in the group. The leader can be at the front, centre or back according to the indications picked up from the physical environment and the group. The leader should be tuned into signs of discomfort, stress or anxiety and alive to possibilities that will arouse interest in, enthusiasm and reverence for, the mountain environment. The leader is at once consultant, counsellor, guide, mentor, chaperone and a source of information, knowledge, skill and experience. The leader is not so much a leader in the traditional sense, but more a person whose experience and resources are at the service of the group.

In companies addicted to internal politics, Machiavelli remains the stuff of day-to-day reality. But Machiavellian management may have had its day. The gentle art of persuasion is finding fashion with managers. The ends no longer justify the means. The means, the subtle management of relationships, are the ends by which future opportunities may be created.

Decision-making styles

To get a good indication of someone’s leadership styles, take a look at their way of decision-making. William C. Miller describes five decision-making styles in common use in his book, “The Creative Edge”:

Whichever way you choose to identify different leadership styles, modern ideas about leadership advocate a flexible combination of all of the styles mentioned above. The leadership skill is knowing when to use each for greatest effect. For example, whilst participation can generally be a good thing and is widely promoted today, it is not always desirable. There may be a need to resolve a crisis urgently or raise standards significantly beyond current expectations. In these cases, respectively, perhaps a more autocratic, and leading from the front, styles would be more appropriate.

Change Management

Change is happening all the time – it appears to be the main consistent feature of life today. ln industry and commerce in generally things have speeded up. The structure of firms is changing constantly – with moves from centralisation to decentralisation and back; merger and de-merger; management buyouts and buy-ins, and the emergence of part-time, contract and temporary workers as a major element in the workforce. The world economic and political scenes are in a state of flux.

In fact, the only consistent thing is that change is here to stay!

Reassuringly, though, change is not new.

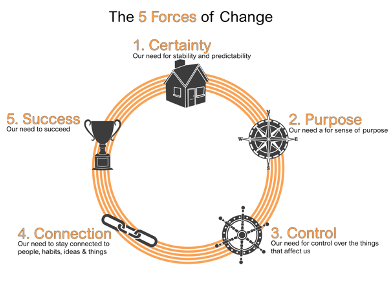

Individuals react differently to change and to different types of change. Partially this depends upon our characters, expectations and conditioning – have we been subject to much change in our lives or little? Is the change going to be good for us or bad (in our perception, not anyone else’s)? What will the consequences of this change mean for us as individuals?

Well managed change can lead to enthusiastic and committed individuals; poorly managed change can lead to de-motivation and stress, sometimes leading to significant loss of the benefits a change process was trying to achieve.

As leaders and managers, it is important that we understand the effects that change has on individuals and on organisations and come up with strategies for handling and managing change successfully.

Change in organisations, whether it involves reengineering, restructuring, merging, responding to market changes, can be complex, dynamic, messy, and scary – and, often, unsuccessful. Some of the major mistakes made by organisations implementing major change programmes:

- Too much complacency. A sense of urgency is required for change. It is vital to muster the necessary effort and commitment. Did you have to fight to get your M&A project on your organisation’s map?

- No powerful guiding coalition. Change requires a coalition of people who, through position, expertise, reputations, and relationships, have the power to make change happen. Who is in charge of your project – is it the CEO, a business line manager, an operations manager or an IT manager? Do they have the power to make it happen?

- No vision. Without vision, change efforts dissolve into a list of confusing, incompatible, and time-consuming projects going in different directions – or nowhere at all. Without a documented strategic plan, it is difficult to disseminate the objectives and strategy of the organisation.

- No communication of the vision. Major change often requires people to make short-term sacrifices. But people won’t make those sacrifices unless they understand why they are required.

- Obstacles that block the vision. Major change, such as an M&A integration, demands action from a large number of people. Many initiatives fail because obstacles are placed in the path of these people. Two common obstacles: the bureaucracy of the company or an influential saboteur.

- No short-term wins. Complex efforts to change strategies or restructure businesses lose momentum if there are no short-term goals to meet and celebrate. Without short-term wins, people give up – or join the resistance.

- Victory declared too soon. After working hard on a change programme, people can be tempted to declare victory too soon. Then their concentration and commitment lag and the company regresses. How may project managers spend ages creating the project plan then fail to get it implemented?

Managerial mindset is behind many of these mistakes. For example, the job of managers is to make sure the organisation keeps humming along smoothly. Therefore, they’re used to avoiding urgency rather than creating it. This means that you must ensure that all your staff understand that the effective and timely management of change is not optional, it is an organisational imperative.

Comfort is not the objective in a visionary company. Indeed, visionary companies install powerful mechanisms to create discomfort—to obliterate complacency—and thereby stimulate change and improvement before the external world demands it.

As long as people are involved there are four vital ingredients which underpin the successful management of change including: leadership, commitment, involvement and recognition. These four ingredients should focus on delivering success through people and not inflicting change on people. Consequently, processes designed to coordinate change efforts across the organisation should be designed to support the actions of people.

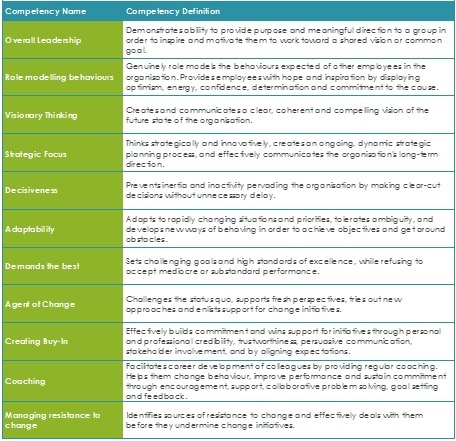

Good leaders appreciate how important it is for them to be role models because they appreciate that change starts at the top – or it doesn’t start. They understand that behavioural practice, not just intellectual knowledge, is the catalyst to trigger the transformation process. If senior management are espousing one thing and doing another the process of change will soon falter. Poor leadership undermines the development of trust, and if left unchecked soon generates widespread cynicism – the quickest way to halt change.

But success doesn’t just rest on the most senior people. Leadership needs to extend down throughout all levels of the organisation. Any individual who manages people is a leader and the creation of followership amongst their people is equally important. The challenge is often getting them to embrace this leadership role.

Without widespread and genuine commitment any change effort is doomed to failure as it gets strangled by existing systems, structures and procedures, supported by people who are committed to keeping their heads down and doing everything to maintain the status quo. The project can simply be choked by the lack of necessary resources and decisions. As such you should try to create a ‘community’ where there is a strong sense of ‘team’ and a genuine desire to work towards a common project goal.

By encouraging people at all levels to become actively involved in the implementation process, you can reduce the inevitable resistance to change and help ensure that you address all the issues. Involvement can also become part of your awareness and training plan as staff actively seek to acquire greater knowledge and understanding of the change in hand. Encouraging the transfer of knowledge between people involved can substantially add to any formal training programmes that you may develop.

Managers must be sufficiently hands-on to give active support but sufficiently hands-off to give teams the space to solve and implement their own solutions. Change requires continuing involvement and commitment over extended periods of time. Without recognising the efforts of your staff, both formally and informally, it is difficult to create an environment in which people remain motivated and committed. The loss of key players during the process of change can seriously undermine your implementation efforts therefore it is important to recognise the work of those involved. This should be a continuous process constantly reminding people that they are valued.

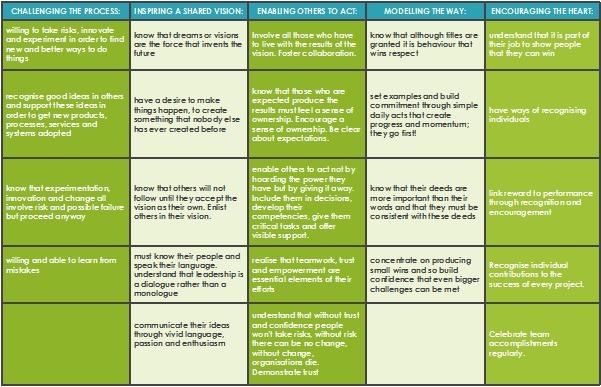

Change Leadership – Key Competencies

Change leadership – key change enablers

- Senior leadership team. It is vital to have them completely on board with the objectives of the programme and that they understand the behaviours they are expected to demonstrate.

- Role models of the new way of working drive the desired new behaviours by demonstrating what the desired behaviours look like in practice.

- Change Champions will be established throughout the organisation, their role will be to advocate the programme and act as a communication conduit between the programme team and the wider organisation.

- Communications are extremely important to ensure understanding a buy-in throughout the organisation of the proposed changes. Communications have been split into two key categories; regular information-based updates and strategic communications in line with the change process.

- Defining roles and responsibilities is important to ensure the accountabilities and responsibilities for the changes are assigned to key roles.

- HR systems and processes are required to drive the new behaviours primarily through reward and performance management.

- Training and Development is required to support the desired changes in behaviours for example a leadership development programme.

A corporate M&A project is a change process, a process that can change people’s working environment as well as their understanding of the organisation of which they are part. It may combine technical solutions and new strategies, as well as developing people with new knowledge and an organisation that operates successfully in a new environment. This presents a number of management problems.

Firstly, particularly in businesses that are not accustomed to working with projects, it is difficult to achieve an understanding of the resources required for a successful project.

There are several reasons why line organisations are reluctant to commit resources:

- They hope that staff can participate in project work on top of their regular job, without any reduction in their original responsibilities;

- They do not understand why the project should take such a long time; and

- They do not understand that a reduction in resources means a reduction in quality.

Secondly, even if there is a real understanding of the need for resources, there are often problems releasing the required people at the required time. Usually people in the organisation are committed on a full-time basis to other tasks and cannot participate in the project unless these other tasks are covered one way or another.

Thirdly is that a project includes people from different backgrounds having different skills and experience. That a project brings together people with different skills is precisely the point of project management; project tasks are solved by precisely this method. However, these people with different skills probably have not worked together previously and this is the challenge of the project manager. Their varied backgrounds, expectations and ambitions can impede the success of a project if no effort is made to form a ‘team’. Time must be devoted to providing opportunities for project members to get to know each other, enabling them to draw on each other’s strengths later on.

It is worth remembering that 9 out of 10 reasons for project failure are people related:

- Insufficient capabilities and/or capacity in execution

- Issues related to leadership, politics, incentivisation, retention, co-ordination, clarity of roles and loss of focus of business as usual

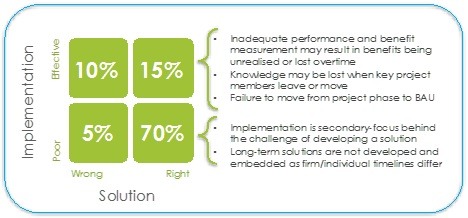

These factors underpin many of the challenges faced when both designing and selecting the right solution for any M&A integration workstream; and most importantly, then getting the implementation completed effectively:

An M&A project is complex with many sections of the organisation involved. The required change and development can be a difficult and unfamiliar concept to many line managers. All-round expertise is required. At the same time problems must be resolved within a relatively short time span if the organisation is not to be weakened competitively or criticised by the public. In some cases, the quality of customer operations and the survival of companies will depend on how well they manage their M&A projects.

Chris Charlton

UK Partner, GPMIP

Chris Charlton is a UK Partner for Global PMI Partners, an M&A integration consulting firm that helps mid-market companies around the world by delivering exceptional consistency, speed, and customized execution on the complex operational, technical and cultural issues that are so critical to M&A success.