Can M&A Help European Airlines Get Out of the Worst Crisis the Industry Ever Faced?

By Manuel Zaccaria, Global PMI Partners

Summary

The airline industry finds itself in a very undesirable situation as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic that brought global travel to a halt. With problems and challenges come opportunities and this is exactly what we’ll discuss in this article. North American carriers outperformed their European peers well before the current crisis for the industry structure in Europe is suboptimal. The crisis of global travel should prompt industry leaders as well as governments in Europe to come up with a new vision for the future of the sector. Consolidation is a way for European airlines to return to sustainable profitability and value creation and post-merger integration will be key to unlock synergies.

Challenges for European airlines started well before the pandemic

Everybody will remember 2020 as the worst year ever for commercial aviation. As a consequence of restrictions imposed by basically every government on the planet, demand by both business and leisure travelers collapsed.

As we look at two of the main metrics of the airline industry—RPK or Revenue Passenger Kilometer which measures demand and ASK or Available Seat Kilometer which measures capacity—we see that global demand declined by 66% year-over-year while global capacity declined by about 57% only[i], highlighting a couple of issues.

First the average industry load factor dropped about 26 percentage points from 80% to 54%. Second, the average industry yield declined 8.7% year-over-year. This means that about one out of two seats that were offered by airlines globally were not sold and those that were sold were sold at an 8.7% discount.

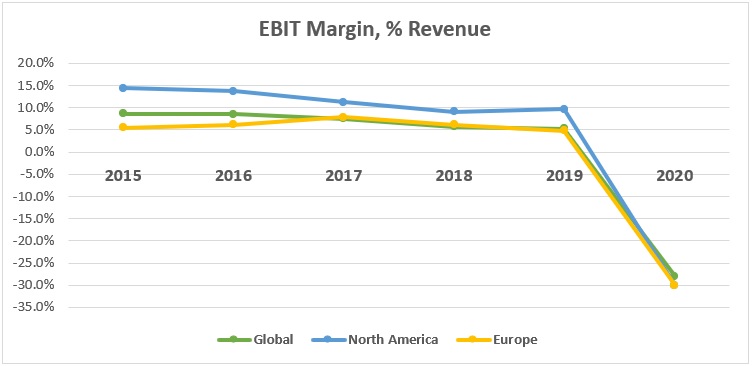

The Covid crisis triggered a serious overcapacity problem which in turn heavily impacted profitability. The aggregate industry-wide EBIT loss was $105 billion in 2020, which sharply contrasts with global operating profits of $43.2 billion in 2019. Average industry EBIT margin passed from 5.2% to -28% globally.

In 2020 both European and North American carriers recorded heavy losses and negative EBIT margins (on average -30% on both sides of the pond), which was predictable given the magnitude of the shock.

What is less obvious is what happened in Europe before 2020 and the Covid-19 crisis. If we break down performance data by macro-region, we observe that both Europe and North America scored an impressive 85% load factor, well above the global average of 80%, but they significantly diverged in terms of profitability. The average EBIT margin in North America was 9.6%, well above the 5.2% global average, whereas in Europe was just 4.8%.

A similar trend can be observed over a number of years prior to 2019, as the following chart shows.

Source: IATA

These data provide a first key insight: in Europe, airlines have a profitability problem which started before the current phase marked by overcapacity.

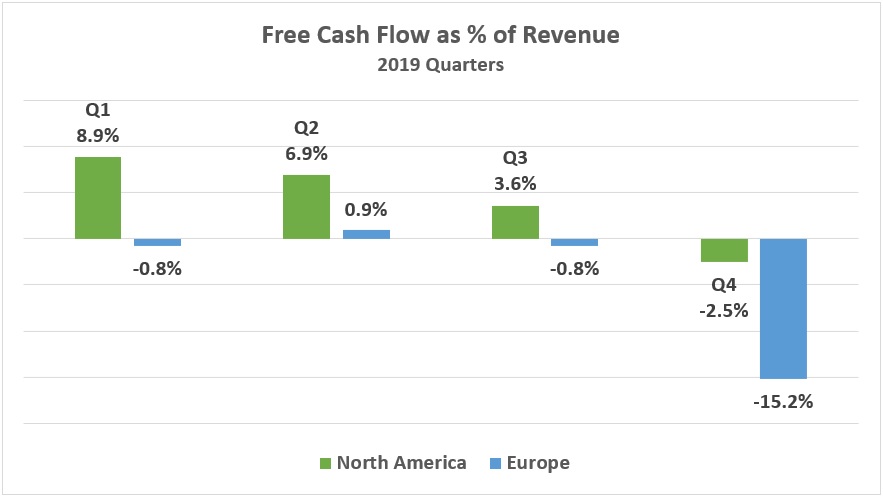

Another way to look at the problem that European airlines face is by looking at their aggregate statement of cash flows. Free cash flow[ii] (FCF) data are the real metric used by financial analysts to value companies and, as the chart below clearly illustrates, North American carriers trumped European ones in terms of FCF throughout 2019. European carriers, on average, failed to create value for shareholders.

Source: IATA (data represent an average of a sample of European and North American carriers)

Industry structure is the main cause behind aggregate underperformance of European airlines

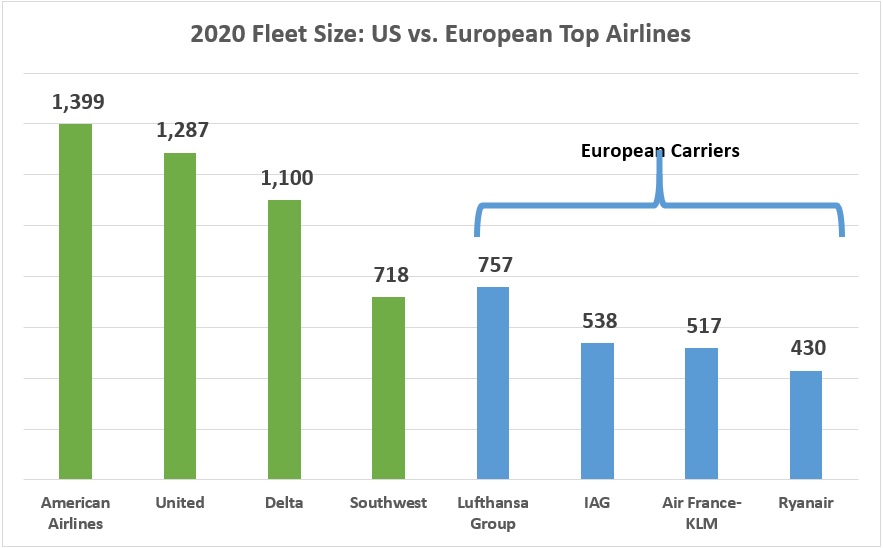

The FCF performance of North American carriers is the result of a consolidation process that started over a decade ago and that led the industry to achieve an optimal structure. In the United States for example, there are three giant carriers (American, Delta, and United) with comparable domestic networks and significant long-haul international operations. Southwest, which is the largest low-cost carrier in the US, does not fly long-haul international routes.

The situation in Europe is very different. Although here too there are three big conglomerates (Lufthansa Group, International Airline Group[iii], and Air France-KLM), they are much smaller than their American peers in terms of fleet size. The following chart illustrates that the fleet of the four largest North American carriers is more or less twice the size of that of the four largest European carriers.

Source: Airlines’ financial reporting (totals include regional aircraft)

On top of the smaller size of European market leaders, there is another problem affecting European carriers: fragmentation within the industry.

In Europe there are several independent legacy airlines in addition to the top three groups. The list includes Turkish Airlines, Aeroflot, SAS, Alitalia, TAP, LOT, Norwegian and Air Europa (the latter recently acquired by IAG). All these carriers use a traditional hub-and-spoke business model which is very similar to that of the three largest conglomerates, with the exception of Norwegian which tried (and failed) to apply the low-cost point-to-point model to long-haul transatlantic routes.

The presence of multiple carriers on specific markets is as good for consumers as bad for companies. Extreme competition erodes margins, undermining the fundamentals of the business which are profitability and cash flow generation.

Ultimately, money-losing carriers may end up canceling routes and shrinking operations which will directly affect both consumers and airline workers. The former will be unable to purchase products that otherwise would be of interest to them while the latter will likely lose their jobs.

To reverse the lose-lose scenario where multiple stakeholders are damaged, it is mandatory to realize positive margins and return to healthy cash generation. A strategy that pursues mergers with competitors is ideal to achieve long-term financial goals that promote growth and business sustainability.

How industry consolidation and post-merger integration can help European airlines improve performance

In a capital intensive, extremely competitive industry, subject to external shocks and multiple risks, size matters. And so does fierce rivalry which contributes to drive load factors and yields down, thus leading to overcapacity and fare deflation respectively.

As history taught us, the US airline industry could return to profitability thanks to consolidation and, as a result of mergers over the past decade, US carriers became the most profitable of the planet. In 2019, over 65% of the industry net profits were generated by North American carriers, which, in contrast, only had a 22.2% share of industry RPKs (that is demand).

Provided the evidence of North America’s consolidation success, legacy airlines in Europe should seriously consider inorganic growth strategies too. And since non-EU investors are not permitted to own more than 49% of a European Union airline, consolidation should occur between EU carriers.

For example, legacy airlines like Alitalia or TAP should logically join forces with Air France-KLM and Lufthansa respectively as they are members of the same alliances (SkyTeam in the case of Alitalia and Star Alliance in the case of TAP) and could enormously benefit from being part of a much larger network.

Mergers would have multiple benefits for airlines. First, they would enable synergies (i.e., economies of scope, economies of scale, cross-selling opportunities) which are crucial to return to profitability and positive cash flows. Second, they would facilitate the launch of nonstop long-haul routes thanks to the “network effect” typical of a hub-and-spoke business model[iv]. Third, they could help optimize their capital structure reducing debt which, again, would benefit FCF generation.

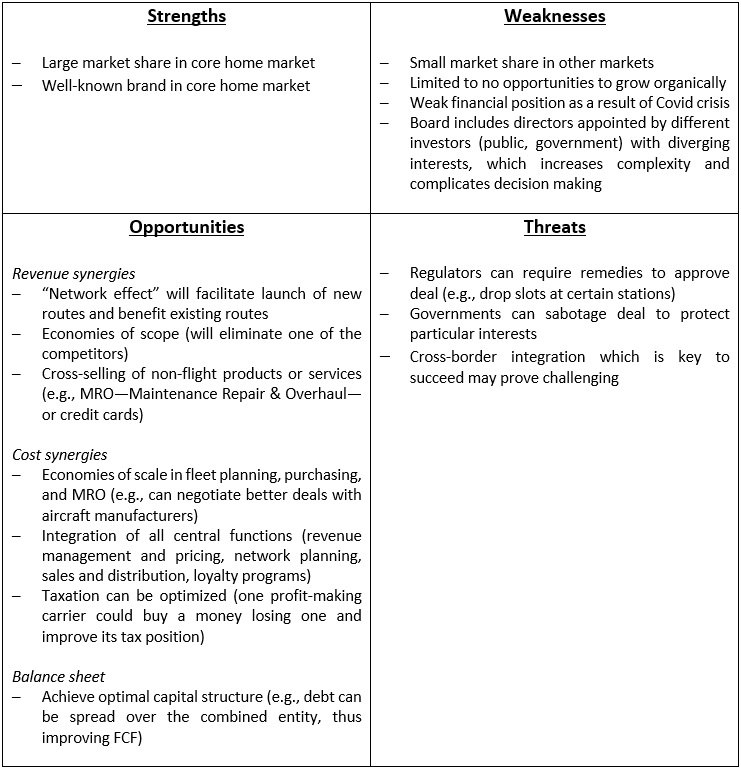

A SWOT framework can help illustrate the considerations that leaders of a European airline could make when considering an acquisition or a merger. In particular it shows that at this point in time weaknesses outnumber strengths but opportunities outnumber threats.

Consolidation plans of European airlines may face three types of threat

First, every time that two airlines join forces and combine operations, they face scrutiny by regulators. Dealing with regulators is indeed normal when it comes to multi-billion euros M&A transactions and does not appear like a factor that is specific to European airlines at this point in time. Threats that are specific to European carriers come instead from two other factors—the return of governments as shareholders and the cross-border integration that will occur after the closing of a deal.

The pandemic brought about a reversal of the privatization process that characterized the past two decades. Given the magnitude of the crisis, governments had to intervene to stem massive scale bankruptcies that could have caused additional damage in terms of job losses and local community impact. Governments’ help did come with strings attached though and will likely delay the transformation process of the sector in Europe.

For example, European market leader Lufthansa Group received a €9 billion loan from Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Belgium in exchange for a 20% controlling stake and a commitment to pay no bonus or dividend until the loan is paid back. An additional condition is that the Lufthansa Group should not use the money it borrowed to engage in acquisitions.

Another heavily indebted carrier, Italy’s Alitalia is in an even worse situation. Alitalia lost money for over two decades and urgently needs to rethink its business model and strategy. After being in special administration for the past four years, a combination of adverse factors including its deteriorating market share in the Italian market, dominated by low-cost carriers, as well as a reputation for being a difficult company to restructure and transform, prevented it from finding an acquirer after the failure of the Etihad project. The Italian government is committed to re-capitalize and re-launch the company to preserve both national identity of the carrier and jobs but the odds it will succeed without being part of one of the three big groups in Europe are small.

In addition to limitations imposed by government shareholders, mergers between European carriers face organizational and cultural obstacles that seriously complicate the post-merger integration and may block the realization of synergies.

Although they all do business internationally, airlines are very centralized companies where all strategic decisions are made by a few leaders at headquarters. This means that in case of cross-border deals between European carriers the acquired airline could lose decision power and autonomy. This aspect might be politically and socially unacceptable during the current historical phase characterized by a rejection of globalization and a return of nationalism. Solid C-level leadership appears as the sole way out of the apparent stalemate. A compelling and well-communicated strategic vision is required to overcome political and national opposition and demonstrate the validity of a consolidation project.

As cross-border deals between European airlines take place, it is crucial to remember that for the success of every post-merger integration, smart management of cultural aspects truly makes a difference. As Global PMI’s partner Christophe Van Gampelaere writes in his essay on “The Role of Culture in Cross-Border M&A”, culture has three dimensions: global, local, and corporate[v]. The second and the third ones are of utmost importance in the case of cross-border M&A between European airlines.

For this reason, a twofold approach is strongly recommended. First cultural awareness should be raised within organizations which are facing a post-merger integration as most people are not really equipped to manage cultural differences. Second a systematic, facts-based approach should be implemented to handle every aspect of cultural integration and nothing should be left to chance.

Ultimately operational and business performance of a combined entity depends on how well teams of people work together. Leaders of the new-born combined entity are responsible for acknowledging the role of culture in corporate organizations and providing employees with the right training, processes, and tools to manage the new post-merger reality.

[i] Source of all industry data is IATA (unless stated otherwise).

[ii] Free cash flow or FCF = Cash flow from operations – CAPEX.

[iii] International Airlines Group or IAG is an Anglo-Spanish holding company which owns multiple airline brands–British Airways, Iberia, Vueling, Aer Lingus, Level, and the recently acquired Air Europa.

[iv] A hub-and-spoke model hinges on a big hub (e.g., AMS for KLM or MAD for Iberia) from which passengers can reach all the destinations of the network. Therefore, a passenger flying from Barcelona to Boston with Iberia will fly first into Madrid to then board a second nonstop flight with direction Boston. In a network structured around hubs every point added on the destination map (for example a new flight from Sevilla) will produce an accretive effect in terms of additional traffic that will flow through the hub and the network to all accessible final destinations.

[v] The aforementioned essay was published in the book “Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions” (Scott C. Whitaker, Wiley 2016).

About the author

Manuel Zaccaria is an associate consultant in Milan, Italy. Manuel has direct airline experience in the US, Europe, and Middle East. He worked at American Airlines and Qatar Airways where he led strategic corporate development and alliances projects which contributed to reshape the industry.

Global PMI Partners, an M&A integration consulting firm that helps mid-market companies around the world by delivering exceptional consistency, speed, and customized execution on the complex operational, technical and cultural issues that are so critical to M&A success.