How Mergers and Integrations with SPACs Create Value for Stakeholders

By Manuel Zaccaria (Associate Italy), with the contribution of Sergio Bruno (Partner Italy) at Global PMI Partners

This article addresses a very hot business topic nowadays–SPACs or Special Purpose Acquisition Companies. We provide an overview of SPAC-related transactions or investments and show how SPACs can generate value for all stakeholders involved. In particular we answer four specific questions:

- What is a SPAC?

- How do SPACs differ from private equity and venture capital funds?

- What is the history of SPACs and what does the current trend look like?

- How can a SPAC merger strategy succeed?

1) What is a SPAC?

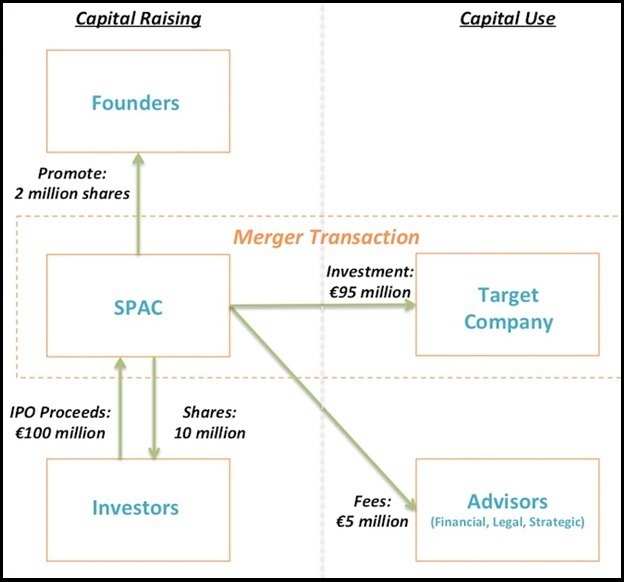

A SPAC is a company as well as a type of alternative investment. To frame it correctly we must acknowledge that there are different perspectives from which to observe it. In particular these perspectives coincide with those of four different stakeholders, each of them with a distinct set of interests and objectives—founders, investors, target companies, advisors.

Let’s start from the point of view of a SPAC’s founders, who are also known as sponsors. They create a company which has no business operations and whose only purpose is to raise capital from the stock market to make an acquisition of a privately held company within a specific industry. Founders are typically experienced executives or private equity leaders who leverage their reputation and industry knowledge to market their investment vehicle to prospective investors. As they complete the SPAC’s IPO, they get a stake in the company, namely the “promote”.

Investors are a key factor in the SPAC equation. For them, a SPAC is an investment opportunity, a unique type of asset, that could be used to diversify their portfolio. As the SPAC goes public through an IPO it collects the investors’ money, typically hundreds of millions, to hold them in a trust. The largest SPAC IPOs bring in proceeds of up to $400 or $500 million. As a matter of fact, investors fund a project which could have high growth potential but is not yet fully defined. For this reason, SPACs are also called blank check companies as indeed at the onset it is unclear what their target company is. The management team (formed by the founders or sponsors) has usually up to 24 months to search a target to merge with. During this phase some SPACs will use a more flexible approach than others. For example, some will invest in businesses which are ESG-friendly only, whereas others could limit risk they take to attract pension funds. In case no target is identified, and no transaction occurs, proceeds from the IPO will be returned to investors. Provided high valuations in the US and Asian stock markets, some investors are of the opinion that value can now be found in private companies. By taking them public, they expect to realize important capital gains.

From the perspective of a target company, cutting a deal with a SPAC has multiple benefits. First, proceeds are usually available earlier than in a classic IPO process. Time to capital market is generally faster as scrutiny by regulators already happened as they performed the pre-IPO due diligence and audit for the SPAC, whose sole asset is cash. Second, the risk represented by market conditions on the day of IPO is mitigated as funds are already available. Third, the risk of dilution for the target is reduced as deals proposed by SPACs are generally not hostile and involve only a minority stake.

The fourth and last stakeholder groups are the SPAC advisors. For them, SPACs are clients who provide significant business in the form of IPO, M&A, legal and other advisory fees.

The chart below will help illustrate the relationship among the stakeholders in terms of how SPACs work through their cash flow. In the following example a SPAC raises €100 million from investors and uses the liquidity to purchase the target company for €95 million. The remaining €5 million are spent for advisory services that are needed to complete the transaction.

2) How do SPACs differ from private equity and venture capital funds?

SPACs belong to the family of alternative investments, like private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) funds, but have very little in common with either of them.

The first big difference is that PE/VC funds invest in a variety of companies at the same time building an investment portfolio, whereas SPACs typically look for one or two target companies to merge with and, upon completing the transaction, dissolve into them.

SPACs and PE funds differ also in the type of companies they target. While the latter typically look for “boring” cash flow machines, SPACs may scout for the next big thing to lure retail investors and do not disdain young companies with disruptive business propositions (e.g., DraftKings).

Another important difference between SPACs and PE/VC funds is accessibility for the general public. While SPACs are public companies that welcome every investor, the PE/VC world is closed to retail investors, as funds typically accept investments from affluent and sophisticated investors only. In the case of PE funds, it is common practice to delist companies they purchase when these are public, which is exactly the opposite of what SPACs do.

A third important difference between SPACs and PE/VC funds is that investors in SPACs have the right to redeem their investment if they disagree with the proposed merger. In fact, after a deal is announced, SPAC shareholders are summoned to vote to approve the deal, which exerts material pressure on sponsors. Conversely, investors in PE/VC funds have limited ability to withdraw funds prior to a specific period.

3) What is the history of SPACs and what does the current trend look like?

SPACs recently gained the spotlight as more and more high-caliber executives as well as celebrities got into this business. However, this investment concept seems to date back several decades. According to INSEAD’s Ivana Naumovska, a SPAC is a form of reverse merger, during which “a successful private company merges with a listed empty shell to go public without the paperwork and rigors of a traditional IPO.” Reverse mergers appeared in the ‘70s and after then came in waves, with the last one peaking in 2010/2011.

In reality, SPACs and reverse mergers or RTOs (Reverse Takeovers) resemble each other but are not exactly the same thing. The former are new companies with no business history (and therefore no risk of carrying hidden liabilities) and actively scout for private companies to merge with and take public (a process known as “de-SPAC”). On the other hand, the latter are dormant shells which could be used by some companies to eschew regulatory scrutiny. In 2011 and 2012 for example, the SEC intervened to delist or suspend over 100 US-listed Chinese companies and issue a warning to investors.

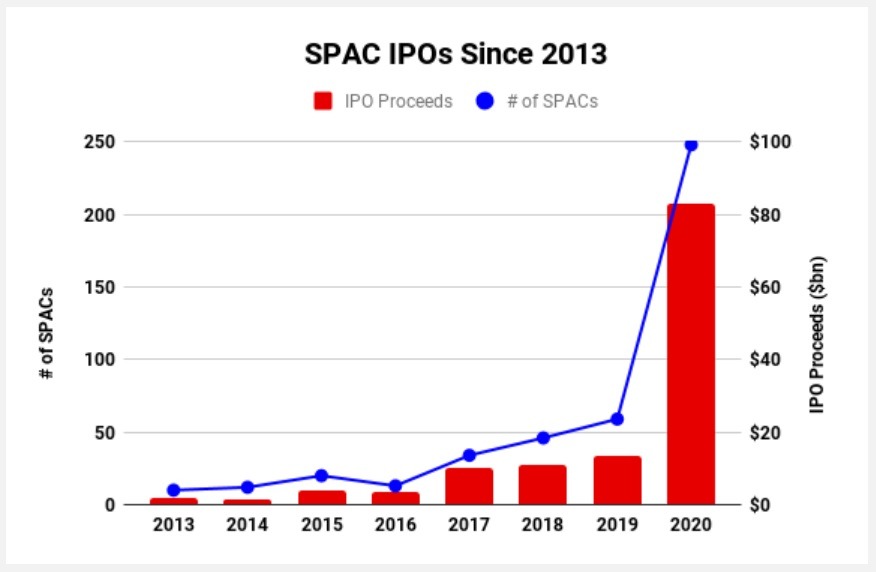

Since then, numbers of SPAC IPOs have progressively increased (see chart below) to reach record levels in 2020.

Source: SPACresearch

Coming to our days, SPACs are materially contributing to boost global M&A to record levels. According to the Financial Times, deals worth $1.3 trillion were agreed the first quarter of 2021, a level not touched since at least 1980. In the US alone, deals involving SPACs topped $172 billion, a quarter of the total.

The trend will likely continue throughout 2021 as cash in the markets is abundant, private equity firms have a lot of dry powder, and many investors look for opportunities beyond some overvalued growth stocks.

4) How can a SPAC merger strategy and post-merger integration succeed?

First off, let’s define what success looks like for SPACs. Throughout the first two or three years post-closing, it is all about stock price appreciation as “going public”, especially during a period of substantial liquidity availability like the current one, will attract the attention (and business) of many more investors.

However, both founders and investors must keep in mind that the historical track record for M&A deals is a mixed one, and as Global PMI Partners’ Scott Whitaker reveals in his M&A Integration Handbook (available on Amazon), approximately 60% of deals fail to create value for shareholders. Deals involving SPACs are no exception and, in this section, we’ll look into drivers behind their success, that is stock price surge.

In summary there are three main drivers of success for SPAC mergers:

– Hands-on industry experience of sponsors;

– Executive incentive and compensation structure; and

– Successful completion of post-merger integration.

The first driver of success is hands-on industry experience of sponsors.

Generally speaking, in the world of M&A, transactions are either strategic or financial. The purpose of the first type is to create value through operational synergies that are coming from business expansion, economies of scale, etc. Oppositely, the purpose of the second type is to invest in undervalued assets to then sell them at a premium.

Transactions involving SPACs are usually of strategic nature. The sponsors typically are subject matter experts of a specific industry, know all the ins and outs of the market they operate in, and have a solid business thesis in mind. Therefore, their contribution goes beyond mere capital supply and includes leadership and strategic vision. When they search a target company to merge with, they look for deals that create value through the realization of synergies. As a result, the new company that is formed offers an enhanced value proposition involving products or services that customers like best and want to buy.

Plus, after merging the companies, at least one of the SPAC’s founders takes an active role in the board of directors, thus ensuring that the implementation of the agreement adheres to the initial strategic vision that inspired the parties throughout deal structuring, due diligence, and negotiations.

A second driver of performance is the right incentive structure for executives.

On top of focusing on their area of expertise, sponsors must be given a proper incentive package that ties their compensation to market performance.

As previously mentioned, the SPAC’s shareholders are called to vote to approve or reject the proposed deal, which exerts an initial positive pressure on sponsors who are incentivized to identify the best target possible and clearly explain the benefits (or synergies) of the combination.

As the deal is approved the industry best practice is to then offer sponsors a combination of equity and warrants as compensation. The former, usually known as “promote,” will be subject to restrictions on transfer for a pre-determined period (the lockup period) during which sponsors are unable to trade their shares. The latter will grant them the right to receive additional shares if the stock price crosses a pre-defined level.

A third driver of SPAC’s success is execution of post-merger integration.

Evidence suggests that integration issues negatively impact M&A deals, undermining synergy achievement in about 50% of the cases.

The key point to remember here is that post-merger integration (PMI) is not business as usual. PMI is additional business that comes on top of business as usual, thus requiring additional resources and work.

During integrations, conflicts of every kind emerge, delaying management decisions and causing integration paralysis. Conflicts have an impact on operations and end up affecting strategic stakeholders like customers, employees, and suppliers. Studies done on customer satisfaction in mergers show that customers expect merging companies to address their issues within 100 days after the closing.

The antidote to spreading conflicts is communication—an aspect that is often overlooked by senior leaders. Communication should be planned in advance and frequently delivered during all stages of the integration process. It should be clear and positive and address concerns and doubts of all stakeholders, thus preventing confusion and anxiety, delays and inefficiencies that could trickle down to customers or suppliers.

The results of a well-planned and well-executed PMI will be captured by operational and financial KPIs (e.g., increase in the number of customers or contracts, retention of key employees, revenue or EBITDA growth) and ultimately reflected in the stock price, the ultimate metric signaling whether a SPAC combination agreement is successful.

| Sergio Bruno | Manuel Zaccaria |

| Italy Partner GPMIP |

Associate |

About the authors

Manuel Zaccaria is an Associate for Global PMI Partners in Milan, Italy. He worked on several cross-border joint venture and post-merger integration projects in the US, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. He developed extensive cross-functional experience in multiple industries.

Sergio Bruno is a Partner with Global PMI Partners. He is a seasoned post-merger integration expert that helps mid-market companies around the world bring their operational, technical and cultural differences into alignment.

Global PMI Partners, an M&A integration consulting firm that helps mid-market companies around the world by delivering exceptional consistency, speed, and customized execution on the complex operational, technical and cultural issues that are so critical to M&A success.